Author Richard Russo hasn’t lived in his hometown for decades, hasn’t even gone back to visit.

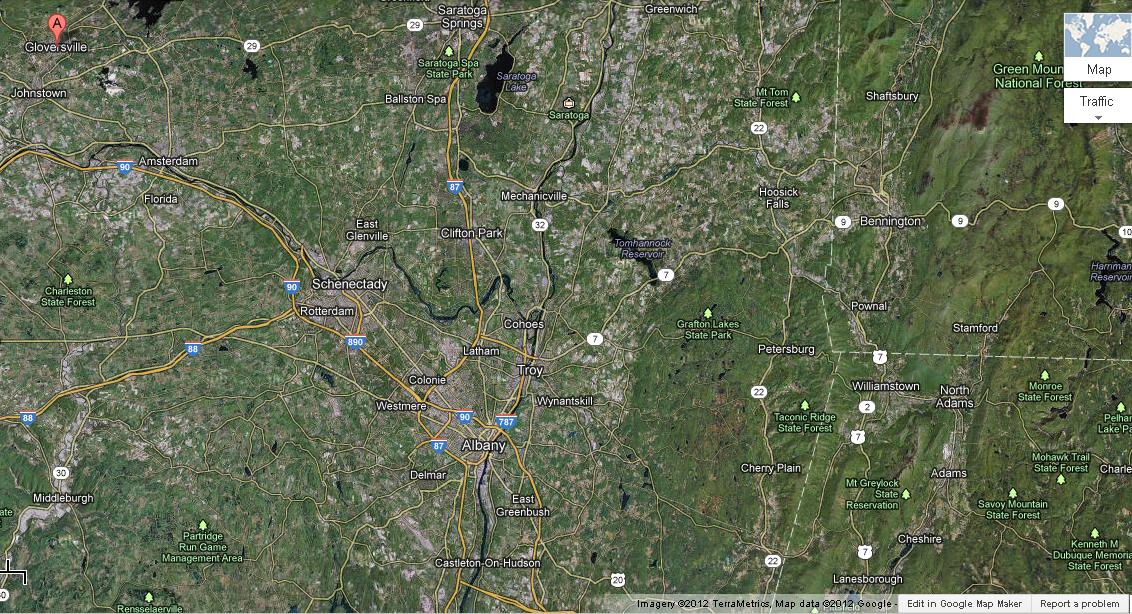

Yet Russo remains intimately tied to Gloversville, N.Y. , setting most of his books in a fading factory town like the one where he grew up, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Empire Falls.”

“In some fairly fundamental way, I never left,” Russo said.

I asked Russo for a Newvine Growing interview not just because he’s my favorite author and I’ve read every one of his books, but because as I’ve wrestled with where we should call home, I was intrigued by his connection to his hometown. I was also curious how his creative process has changed since he went from a college professor who moonlighted as a writer to a full-time writer who’s “won a prize.” (He would never actually say the word “Pulitzer.”)

After keynoting the American Booksellers Association with a passionate message about the threat posed by Amazon, Russo met me at the Grand Central Oyster Bar. He nursed a cough with a cold draft beer, and talked with me for an hour and a half before heading off to a reading for his new book, “Interventions.”

Two Gloversvilles

Seeking a better life drew Russo’s maternal and paternal grandparents to Gloversville, an upstate New York town where leather was tanned and turned into nearly all the leather gloves sold in the U.S. But as glove factory jobs disappeared, “It was commonly accepted of my generation that we were going to have to leave.”

Russo’s mother not only urgently wanted him to leave, but wanted to go herself. She even hatched a plan to follow her only son when he enrolled at University of Arizona — only to return to Gloversville, as she always did.

“There were always two Gloversvilles for her,” Russo said. When she was there, it was claustrophobic, with no hope and no opportunity, but it was also her safety net, and when she left, she yearned for it as though she’d been unfairly expelled.

“She was never able to resolve that paradox,” he said. “She passed that on to me.”

“I love that town and everyone in it like she loved it when I’m not there.”

Russo described feeling that tension each summer, when he’d return from college and work road construction with his dad. He told NPR about it in 2007:

“At the beginning of the summer I would think, ‘God, I don’t know if I can get into those rhythms of life again,” Russo says. “But by the end of August, I would be so thoroughly subsumed into that other life — a very hard life that my father lived. But then at the end of the day, sitting at a bar and watching those long-neck bottles of beer line up sweating in front of you, and I would think to myself, ‘Do I really want to go back to the university?’

“And as a result of doing that every summer, I think I bifurcated in some way. I’ve always thought that there was some other version of me sitting on a bar stool.”

Russo said he liked the construction guys, who he described as good-natured drunks, bar brawlers filled with rage about how hard they worked for so little.

“Your life where you end up seems inevitable, but I do have that sense of, ‘There but for the grace of God,'” he said.

Russo’s 2007 novel “Bridge of Sighs” focuses on high school friends who are now adults — one of the men an artist living in Venice, another still in his hometown, married to his high school sweetheart.

“I feel almost perfectly placed equidistantly between these two characters,” Russo said.

“Interventions” is a collection of four short stories, each with an illustration by Russo’s daughter, Kate. The story “High and Dry” tells the story of Russo’s family in Gloversville, which he says this fall’s “Elsewhere” will explore in greater depth.

“I’m calling it a memoir because I don’t know what else to call it,” he said, adding that he’d recently talked to his author friend Andre Dubus about writing memoirs, and that they’d discussed the goal not being sharing something you know but trying to figure something out.

Dubus said in a conversation with Russo and the Portland Phoenix:

Honesty, Rick, I’m really glad I was writing fiction a lot of years before I started to turn the camera onto myself. It makes me think of Louis Pasteur injecting his whole body with germs. He had enough faith that he would actually survive and in fact, perhaps, triumph with the right attitude, which I think is truth seeking.

Resources and challenges

Russo was a fiction instructor at the Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and a professor of creative writing at Colby College in Waterville, Md. Russo wrote his first book, “Mohawk,” while teaching full time, but his novel wasn’t set in a quaint college town — it’s in a city much like Gloversville where the tanneries are closing.

He described the old book-of-the-month series “The Story of Civilization” as having the central premise that civilizations flourish when they have resources and challenges.

“I have thought that same thing holds for artists,” Russo said. When he taught at Colby, he saw kids who’d had every advantage and who carried a broad sense of entitlement. It made him appreciate his own background.

“It opened my imagination to almost anything I would want to write about,” Russo said of Gloversville.

Struggling towns play such an important role in Russo’s writing that in 1995, he gave a lecture to Warren Wilson MFA students called Place in Fiction. My friend, Mary Jean, shared a cassette of the lecture while she was a Warren Wilson student — and since 1995 predated YouTube and cheap digital cameras, I can’t share a video clip here. But it struck me as a writer that Russo thought of these towns as a character unto themselves, not just the backdrop where people happened to do things.

So much harder to please

Russo won the Pulitzer in 2002 for “Empire Falls,” which he said added pressure to his work. While he jokes, “I come from a long line of bullshitters,” he wanted to produce stories worthy of that award.

“As I get older, I am so much harder to please,” Russo said. He used to suffer through a “grotesque first draft,” patient with revising and improving it later, but now he works much slower, finessing each word and sentence as he goes.

“I’d love to be able to go back to those halcyon days of letting go,” Russo said.

Russo retired from teaching after he discovered screenwriting — his novel Nobody’s Fool became a movie starring Paul Newman, and was nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Actor in a Leading Role (Newman) and Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrxucPR9vRc]

“I miss the students but not the classroom,” Russo said. “Screen writing offered me something I didn’t know.”

It also kept Russo from becoming a hermit, something Russo’s wife feared might happen if he left teaching to write full time. He began working with the screenwriter and director Robert Benton, which Russo compared to going back to graduate school. He relished the collaboration and the challenge.

He also collaborated with his artist daughter, Kate, on what some have described as an anti e-book, but what Russo calls a celebration of printed books. “Interventions” is printed in the U.S. on paper from sustainably harvested forests, featuring full-color illustrations of each story.

It’s a family affair, as Russo’s other daughter, Emily, sells books at the Brooklyn bookstore Greenlight. They all share a passion for books and for ink on pages. Greenlight hosted the reading Russo headed off to after our interview.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGdGQLn2LRQ]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rCbqUq07YFw]