This is the second installment of a new occasional series on writers — how and why they write, what inspires them and how they overcome challenges like writer’s block and rejection.

Today we get a baker’s dozen of questions and answers with Jim Ottaviani, who writes graphic novels about complex scientific concepts like the space race and the development of the atomic bomb. Like Lara Zielin earlier this month, Jim gives us a peek into how he does what he does.

1. What have you written?

In chronological order:

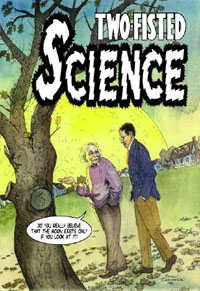

Two-Fisted Science: Stories About Scientists (1997)

Dignifying Science: Stories About Women Scientists (1999)

Fallout: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, and The Political Science Of The Atomic Bomb (2001)

Suspended In Language: Niels Bohr’s Life, Discoveries, And The Century He Shaped (2003)

Bone Sharps, Cowboys, And Thunder Lizards (2005)

Levitation: Physics And Psychology In The Service Of Deception (2007)

Wire Mothers: Harry Harlow And The Science Of Love (2007)

T-Minus: The Race to the Moon (2009)

I also edited Charles R. Knight: Autobiography Of An Artist, which came out in 2005.

Coming up are Feynman (2011; it’s about Richard Feynman), The Imitation Game (2012, most likely; it’s about Alan Turing and will be serialized first at Tor.com), and Primates (2012 or 2013; it’s about Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Birute Galdikas and Louis Leakey).

2. What do you wish you’d written?

I’d never thought about this before, and there are a couple of ways to answer the question. One way, which I’m sure you didn’t intend, is to choose a book I wish I’d written because I had lived the life required of the writer. And the first one that comes to mind here is “Nice Guys Finish Last,” by Leo Durocher. That man had one heck of an interesting career: You could do worse than having your NY Yankees teammate Babe Ruth nickname you “The All-American Out,” playing shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers and the legendary 1934 St. Louis Cardinals “Gashouse Gang,” managing teams starring Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and Ernie Banks, and writing a book I loved as a kid and still love today.

But again, that’s probably not what you meant. Even so, I’m still not going to answer your question correctly because there are too many to count, and I don’t want to imply that I could have written any of these. Because I don’t think I could have. That disclaimer aside, the books that immediately come to mind are Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” (because if you’re only going to write one book, make it this good), “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” by Richard Rhodes (my ideal for engaging history), and on the comics side of things, “Watchmen” (which should need no introduction) and Howard Chaykin’s “American Flagg!” (because it opened my eyes to density and complexity in serial storytelling).

3. Who or what inspires you?

Scientists and their discoveries are the two main (and most obvious!) things. Strip away what they’ve done, and what engineers have made of their work, and we couldn’t be talking right now. Heck, we’d probably be dead, since just 100 years ago you and I would be well past the average life expectancy of a typical human. We’d sure feel and look much older, even if we weren’t already dead and gone…

But just as inspiring to me (and without the morbid subtext I just stuck science with…sorry, science!) is the medium of comics itself. The storytelling potential of words and pictures working together — or at cross purposes, if done intentionally — on the page or screen is infinite.

At the same time, what you can do is also constrained by what will fit on that page or screen, so the writer and artist are forced to make hard choices: How the first impression of all the panels taken together can influence how they’re read sequentially, the ability of art to add emotional depth to the text, the choice of colors and typefaces and line weights and borders…and I could go on about this until you’d want to punch me in the arm and say “shut up already!”

Anyway, those hard choices are good for a writer, as well, and inspire creativity.

4. How do you answer when someone asks you, “What do you do?”

I write comics about scientists. When I started doing this, people didn’t get it. They do now.

(If the question comes in the context of my day job, I say I’m a librarian. Everybody gets that, though their assumptions about what I do on a day-to-day basis are probably wrong.)

5. When do you most enjoy writing? What do you enjoy least?

Most of the enjoyment is retroactive. “I hate writing. I love having written,” isn’t quite true, since some days when I loved writing were followed by days of hating what I wrote. But making something new is always enjoyable, and even when it’s difficult and I don’t enjoy it, it’s not hard like a tour of duty in Afghanistan is hard. So it’s pretty good, even when it’s not going well.

I find revision difficult. Not because I write so beautifully that it’s torture to remove a single word, but because of the structured nature of comics. Much more than in straight prose, where nothing is revealed without actual reading, even and odd pages and what you show on them matter. (And what you hide. Do you have a visual surprise to spring on a reader? It’s best if you can put it on an even-numbered page, so it’s hidden from view until the moment you want it seen.)

Like it or not, each even-odd spread will function as a scene, at least visually, so when you find you have to add something or take something out that affects the reading experience… that cascades through the rest of the book. That’s the down side of the power of images; they’re so compelling that you have to be very careful how you use them.

6. Describe your favorite writing environment.

A room in my house, surrounded by books. Ideally, it would not be surrounded by internet access, but I don’t have the discipline to turn that off completely. I’m trying to learn how to use the following magic spell: “fact/detail TK”. Put that in the MS and you keep the story flowing, but more often than not I’ll reach a point where a fact/detail is needed and switch over to the web browser and look up the distance between Manchester and London, or the date of the first published description of the telectroscope and then find myself sucked down the rabbit-hole labeled Important Research That Must Be Done Now! and lose an hour when I should have been working on telling the story and saved the research bit for later.

In short, I would waste a lot less writing time if I didn’t like to read.

7. How do you budget your time for the creative part of writing versus the business side — marketing, communicating with your agent or editor, tracking finances, etc.?

I have no plan. I drop just about everything when my agent or editor calls, since they do indeed seem to have a plan, real deadlines, and needs. So I try and make sure that what they want gets done as soon as possible. The same is true for the business aspect of writing, though it’s easier since I seem to be able to deal with the numbers side of things without much problem. (I have a, how shall we say, robust spreadsheet for keeping track of sales and royalties and the like. My background helps with this.) And I am such a poor marketer, my time budgeted for it is small. I don’t say that with any pride…

8. How do you deal with writer’s block?

Deadlines are the cure, so if I don’t have one via a contract, I make one up. I seem to be able to trick myself into believing these dates. I wish I could trick myself into self-promotion or internet abstinence…

9. How do you deal with rejection?

I’ve met with very little outright rejection — I can think of only one piece submitted for publication that was completely scrapped — so I deal with it by being lucky, I guess.

More seriously, when I’ve written something that needed a lot of work to fix I do the obvious and give it another try based on the feedback from the editor. They’re almost always right about some aspect of the piece not working, and even when I think they’re not the editors I’ve had have been so professional and helpful and so clearly dedicated to making the story better that we’ve found a way to make things work for both of us. Here again, I’ve been lucky!

10. Do you outline a structure before you start writing or do you just let the story unfold?

I prefer the latter, but lately I’ve been asked to outline before I start. The finished piece doesn’t always look like that outline, but I’m growing to like the process (or at least the results), as it helps me find places for the important bits early on. That means I don’t have to toss out as many great scenes during revisions, which is a relief.

11. Do you know immediately when you’ve written something good?

That presumes I’ve written something good.

But, no, I don’t know immediately, and don’t often know in retrospect either. With some distance I can decide if I like it, but that’s not the same thing.

12. Did anything about your approach to writing change after you were first published?

No. I self-published my first books — you can do that in comics without the stigma, much less distribution problems, that’s attached to it in the prose world — and I still work the same way now that I’m getting advances and working with large publishing houses. I think the results are better now, though. I hope they are, and that I’ve improved!

But it’s still idea -> research -> think -> research -> rethink -> write -> pause -> rewrite with a healthy dose of “repeat as necessary” (and “procrastinate”) mixed into the above stages.

13. Why do you write?

This will sound clinical (or at least very much like an engineer wrote it) but it’s true: Beyond the enjoyment anyone can get from practicing a craft, I practice this particular craft because it’s an efficient way of getting ideas I think are important across to other people.

You could say the same thing about the corollary to writing: Beyond simply enjoying stories, which I do, I love to read because it’s such a wonderful way of learning about people, places, and things. (I could have just said nouns, I suppose…) Real life is fabulous and I wouldn’t trade it for anything, but it’s so inefficient.

Just kidding.

Mostly.