I’ve already seen numerous takes on the “laid off workers decide to pursue new path” story. I blogged about it a while back, linking to a few versions the Times had done, including focusing on white-collar professionals deciding to become disc jockeys. (Why that career and not massage therapists or sign-language translators? Who knows.)

A story in the Washington Post last weekend interviewed several people who’d lost their jobs and decided to do something more rewarding. Like many such stories, it gave significant ink to those burnt out by corporate America who choose to start their own businesses instead.

Elizabeth Razzi’s story includes Maxine Gill, who was laid off from a marketing job and opened a business hiring and placing nannies and tutors. Gill is quoted as saying:

“If I were still in corporate America, I would have to work extra hard, and I would have to travel. You’ve got to do more now because of the economic recession to keep your job,” she said. “People like me, who have been laid off, are reassessing what they want out of life and what they need to do.”

I took a class in business school on compensation and employee motivation. It got me thinking about several basic concepts of business, including what it means to be an employee.

If you work for someone else, whether it’s a huge corporation or you’re #2 in a two-person office, part of the advantage is you don’t bear as much of the risk. You don’t take out the business loan or invest in R&D, you get the stability of a paycheck even if sales aren’t steady.

You also don’t typically share in the upside benefits. While some early employees of Microsoft or Google might have been in the right place at the right time, generally the bosses take the risks and enjoy the rewards.

Our professor, John Tropman, simplified this notion by saying employees sell their services wholesale, then their employer resells them at a retail mark up, keeping the profit. The margin is most evident in professions like law or real estate, where the customer pays a price and the person performing the work gets just a share of that fee. Some of it goes to cover expenses – rent, supplies, marketing, insurance. Often a big chunk goes to the people at the top.

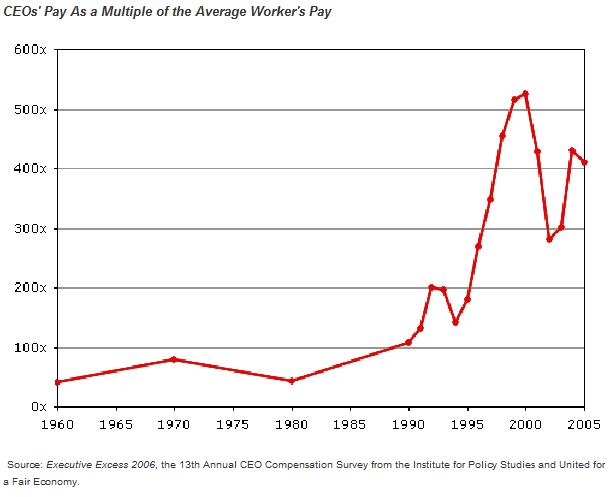

In recent years, the disparity between what low-level employees earn and what corporate execs make has greatly widened. These data at the right are a little dated, and they come from a lefty organization — but even if you assume they’ve skewed the numbers and you cut the percentages in half, they still illustrate a huge shift in American pay in the last generation.

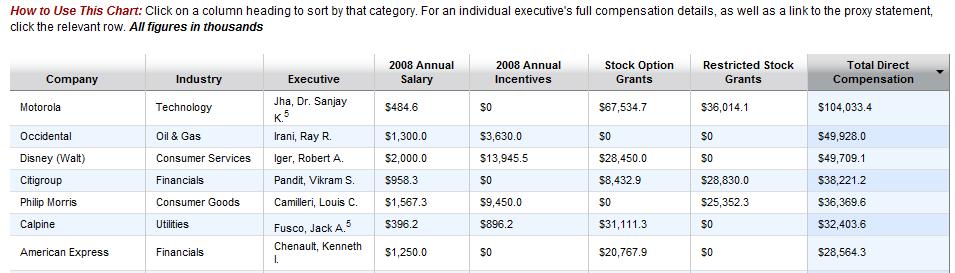

If you want a less liberal view of what CEOs made in 2008, check out this chart by the Wall Street Journal.

I think this is part of what’s fueling this recent interest in entrepreneurship. Maybe you were willing to sell your labor wholesale, giving up the retail mark up in exchange for a greater sense of job security — but getting laid off might cause you to redo the math.

Perhaps you might be willing to take on some of that risk your employer used to bear in exchange for getting to keep a greater share of what your labor is worth?

Maybe seeing more and more of your loved ones losing their jobs at companies where the CEOs continue to take home seven figures, or more, might get you thinking – whose labor is going into paying that salary? His? Or all the people who sold their work wholesale?

Has the recession gotten you thinking about starting your own business? Does it seem like a safer bet than getting laid off or does it feel too scary to carry all the risk?