This post continues an occasional series on writers — how and why they write, what inspires them and how they overcome challenges like writer’s block and rejection.

Previously we’ve heard from Jim Ottaviani, Lara Zielin and Jennifer Worick.

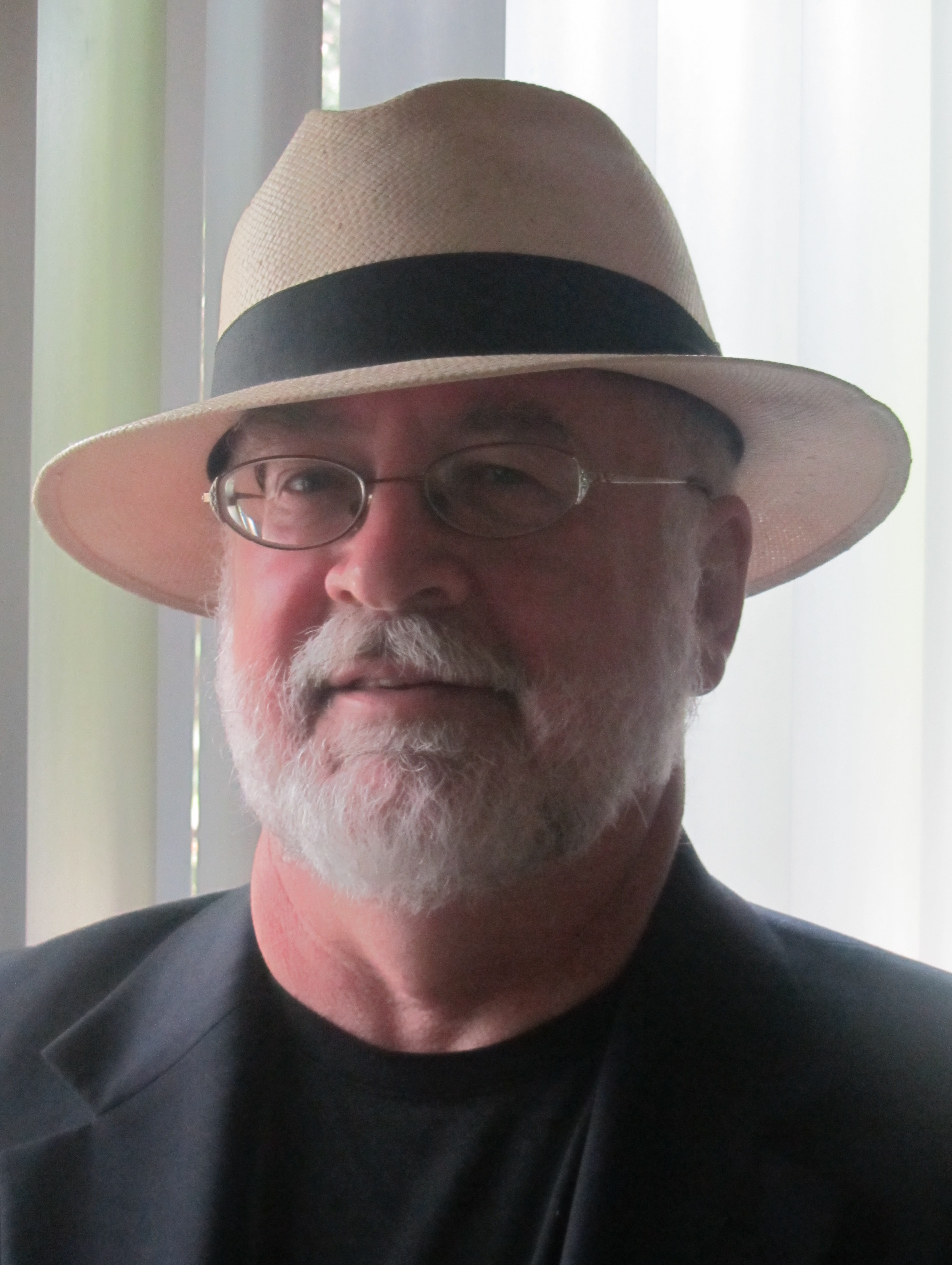

Today’s Q&A features Bruce DeSilva, a retired journalist now putting his writing skills to work in longer form. From his bio:

Bruce DeSilva worked as a journalist for 40 years before retiring to write crime novels full time. At the Associated Press, he served as the writing coach, responsible for training the wire service’s reporters and editors worldwide. Previously, he directed an elite AP department devoted to investigative reporting and other special projects. Earlier in his career, he worked as an investigative reporter and an editor at The Hartford Courant and The Providence Journal.

Stories edited by DeSilva have won virtually every major journalism prize including the Polk Award (twice), the Livingston (twice), the ASNE, and the Batten Medal. He also edited two Pulitzer finalists and helped edit a Pulitzer winner.

He and his wife Patricia Smith, an award-winning poet, live in Howell, NJ, with their granddaughter Mikaila and an enormous Bernese Mountain Dog named Brady.

1. What have you written?

In my first crime novel, “Rogue Island,” someone is systematically burning down a Providence, R.I. neighborhood. Liam Mulligan, an investigative reporter at a dying newspaper, thinks the police are looking for the culprit in all the wrong places; and people he knows and loves are perishing in the flames. As the city burns, it’s up to him to find the hand that strikes the match. The book, which is being published by Forge on Oct. 12, has received sensational pre-publication reviews.

The sequel, tentatively titled “Cliff Walk,” features all the same characters (except for the ones that got bumped off); and it’s nearly finished.

My reviews of crime novels have appeared in The New York Times Book Review section and are published frequently by The Associated Press.

2. What do you wish you’d written?

It’s hard to know where to begin. I’m a great admirer of Daniel Woodrell and Thomas H. Cook, two brilliant crime novelists who succeed at everything except making the best-seller lists. James Lee Burke, Kate Atkinson and Ken Bruen have written paragraphs that take my breath away. But the opening passage of John Steinbeck’s “Cannery Row” is my favorite in all of English.

(Read the first page on Amazon)

3. Who or what inspires you?

People do. Human beings are endlessly interesting if you just learn to pay attention.

For example, back when I was working as a reporter in Providence, some city highway department workers got caught stealing manhole covers and selling them as scrap for seven bucks apiece. And I thought, this is AMAZING! If their boss had asked them to move those heavy things from one side of the warehouse to the other, they would have filed a grievance. But stealing them, loading them onto a truck, unloading them at a scrap yard, and selling them for seven bucks each was too tempting to resist. (Yes, that incident made it into “Rogue Island.”)

Just the other day, I attended a family gathering in central New Jersey. There, one of my daughter-in-law’s uncles proudly displayed an enormous diamond pinky ring he’d just bought for himself. “Why on earth did you buy THAT?” someone asked him. “Because,” he said, shrugging and pausing for effect, “I’m ITALIAN.” I knew immediately I would have to use that.

4. How do you answer when someone asks you, “What do you do?”

I’m a retired journalist who writes novels and teaches journalism part-time at Columbia. I’m working harder now than when I was working.

5. When do you most enjoy writing? When do you enjoy it least?

Sometimes the writing comes easy. The characters come alive on the page. Unbidden, they do all kinds of interesting stuff and say cool things to one another. As a writer, I feel like I’m just taking dictation. THAT’s when it’s fun.

Other times, the characters want to hide out in their rooms and sulk. I beg them to come out and do something. I ask them to talk to me. They refuse. That’s when writing is work. But I don’t give up. I kick down their doors, drag them out, handcuff them to straight-back metal chairs, shine a bright light in their eyes, and make the buggers talk.

6. Describe your favorite writing environment.

I sit in an ergonomically correct chair at a desktop computer in a cluttered office on the second floor of our house in central New Jersey, a bottle of whiskey by my side.

My wife Patricia Smith, one of our greatest living poets, writes in a tidy library downstairs. But sometimes she comes upstairs, plops her laptop at the other end of my long desk, and we write together. Mostly we do so in silence, finding comfort in each other’s company. Occasionally we interrupt one another, asking for advice on a word or a passage. Those are the good times, made even better when our Bernese Mountain Dog wanders up the stairs, sits on my feet, and puts his huge head in my lap.

Here Bruce shows us around his home office:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuLYbS3g0gw]

7. How do you budget your time for the creative part of writing versus the business side – marketing, communicating with your agent or editor, tracking finances, etc.?

I’ve been trying for the last six weeks or so to finish my second novel, but I am continually being interrupted by the business of promoting the first book, which is about to be released. So I don’t have a good answer for this.

8. How do you deal with writer’s block?

I spent 40 years working as a journalist. Journalists write every day, whether they want to or not. We journalists aren’t ALLOWED to have writer’s block. We think that writer’s block is for sissies. We put our butts in the chair and write.

9. How do you deal with rejection?

A rejection is not a commentary on whether a book is good. It’s a commentary on whether publishers think a book is marketable. A lot of crap makes the best seller lists while other crap never sees the light of day. Some fine books sell well while others go begging for a publisher. There is no logic to it, so don’t bother trying to figure it out. When my agent was shopping my first book, I asked a lot of publishers why some books sell and others don’t. The standard answer: “If you could explain that to us, we could all make a lot of money.” In other words, there’s no point in taking a rejection personally.

10. Do you outline a structure before you start writing or do you just let the story unfold?

There are, of course, two schools of thought on this. Some writers outline obsessively. Others, like Elmore Leonard, never touch the stuff. There’s no right or wrong way to do it. You do what works for you.

Me? I’m with Leonard. I begin with a general idea of what the book will be about. For example, I began “Cliff Walk” (the one I’m finishing now) with the notion of juxtaposing the two extremes of Rhode Island society – the Newport mansions and the legal (until recently) prostitution business in the state. I just threw those two worlds together, set my characters in motion, and waited to see what would happen. A lot did.

11. Do you know immediately when you’ve written something good?

My 40 years in journalism—about a quarter of them spent working as a writing coach—have left me very clear-eyed about my own work. I know when something is good. I know when something is bad. And I know when I’ve written something that I could get by with, but that isn’t good enough to satisfy me. That doesn’t mean I always know how to fix it, however.

My 40 years in journalism—about a quarter of them spent working as a writing coach—have left me very clear-eyed about my own work. I know when something is good. I know when something is bad. And I know when I’ve written something that I could get by with, but that isn’t good enough to satisfy me. That doesn’t mean I always know how to fix it, however.

Lucky for me, I’ve got that brilliant poet living in the same house. Patricia’s style is nothing like mine. Her poetry and prose are rich to the point of being sensual. Mine can be spare to the point of sensual deprivation. I rely on her to help me make my writing more descriptive and lyrical. I help her make her poetry tighter and crisper. Our stylistic differences are what make the partnership work.

Of course, the best part is when I type a sentence and it comes out just the way I want it the first time. When I sat down to start “Cliff Walk,” the first sentence I wrote was this: “Attilla the Nun thunked her can of Bud on the cracked Formica tabletop, stuck a Marlboro in her mouth, sucked in a lung full, and said: ‘Fuck this shit.’” And I thought: Yeah, I can write this book.

12. Did anything about your approach to writing change after you were first published?

No. There is always the temptation to second-guess the market, but that’s a fool’s errand. One of these days, some poor bastard will finish a vampire novel at the very moment teenage girls everywhere lose interest in the subject. The late Robert B. Parker taught me this: “You write what you can.”

13. Why do you write?

Forty-six years ago, as I was heading off to college as a geology major, my high school English teacher pulled my parents aside and told them I would eventually find myself writing from compulsion. Turned out he was right.

I write because it’s what I do; I write because it’s who I am; I write because it’s the way I process experience and come to terms with my world and the people in it. And, as Elmore Leonard says, it’s also good to get paid.

Journalist turned novelist Bruce DeSilva on how and why he writes